Abstract

Summary

We examined the association between marital life history and bone mineral density (BMD) in a national sample from the US. In men, being stably married was independently associated with better lumbar spine BMD, and in women, more spousal support was associated with better lumbar spine BMD.

Introduction

Adult bone mass may be influenced by stressors over the life course. We examined the association between marital life history and bone mineral density (BMD) net socioeconomic and behavioral factors known to influence bone mass. We sought evidence for a gender difference in the association between marital history and adult BMD.

Methods

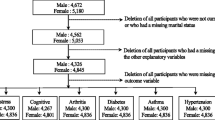

We used data from 632 adult participants in the Midlife in the United States Study to examine associations between marital history and BMD, stratified by gender, and adjusted for age, weight, menopausal stage, medication use, childhood socioeconomic advantage, adult financial status, education, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Results

Compared to stably married men, men who were currently divorced, widowed, or separated, men who were currently married but previously divorced, widowed, or separated, and never married men had 0.33 (95 % CI: 0.01, 0.65), 0.36 (95 % CI: 0.10, 0.83), and 0.53 (95 % CI: 0.23, 0.83) standard deviations lower lumbar spine BMD, respectively. Among men married at least once, every year decrement in age at first marriage (under age 25) was associated with 0.07 SD decrement in lumbar spine BMD (95 % CI: 0.002, 0.13). In women, greater support from the spouse was associated with higher lumbar spine BMD.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that marriage before age 25 and marital disruptions are deleterious to bone health in men, and that marital quality is associated with better bone health in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

USPSTF (2011) Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 154:356–364

Gruenewald TL, Karlamangla AS, Hu P, Stein-Merkin S, Crandall C, Koretz B, Seeman TE (2012) History of socioeconomic disadvantage and allostatic load in later life. Soc Sci Med 74:75–83

Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH (2001) Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:4770–4775

Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS (1997) Price of adaptation–allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Arch Int Med 157:2259–2268

Foundation NO (2013) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B, Looker A, Marcus R, Matkovic V, Weaver C (2000) Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int 11:985–1009

Crandall CJ, Merkin SS, Seeman TE, Greendale GA, Binkley N, Karlamangla AS (2012) Socioeconomic status over the life-course and adult bone mineral density: the Midlife in the U.S. Study. Bone 51:107–113

Dupre M, Meadow SO (2007) Disaggregating the effects of marital trajectories on health. Journal of Family Issues 28:623–652

Lillard W (1995) Til death do us part: marital disruption and mortality. Am J Sociol 100:1131–1156

Hope S, Rodgers B, Power C (1999) Marital status transitions and psychological distress: longitudinal evidence from a national population sample. Psychol Med 29:381–389

Uecker JE, Stokes CE (2008) Early marriage in the United States. J Marriage Fam 70:835–846

Karlamangla AS, Mori T, Merkin SS, Seeman TE, Greendale GA, Binkley N, Crandall CJ (2013) Childhood Socioeconomic Status and Adult Femoral Neck Bone Strength: Findings from The Midlife in the United States Study. Bone

Brennan SL, Pasco JA, Urquhart DM, Oldenburg B, Wang Y, Wluka AE (2011) Association between socioeconomic status and bone mineral density in adults: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 22:517–527

Farahmand BY, Persson PG, Michaelsson K, Baron JA, Parker MG, Ljunghall S (2000) Socioeconomic status, marital status and hip fracture risk: a population-based case–control study. Osteoporos Int 11:803–808

Meyer HE, Tverdal A, Falch JA (1993) Risk factors for hip fracture in middle-aged Norwegian women and men. Am J Epidemiol 137:1203–1211

Nabipour I, Cumming R, Handelsman DJ et al (2011) Socioeconomic status and bone health in community-dwelling older men: the CHAMP Study. Osteoporos Int 22:1343–1353

Gove WR (1984) Gender differences in mental and physical illness: the effects of fixed roles and nurturant roles. Soc Sci Med 19:77–91

Ross M, Goldsteen (1990) The Impact of the Fam on Health: The Decade in Rev J Fam and the Fam 52:1059–1078

Dienberg Love G, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD (2010) Bioindicators in the MIDUS national study: protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. J Aging Health 22:1059–1080

Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC (2004) How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Radler BT, Ryff CD (2010) Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. J Aging Health 22:307–331

Schuster TL, Kessler RC, Aseltine RH Jr (1990) Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Am J Community Psychol 18:423–438

Riggs BL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Mazess RB, Offord KP, Melton LJ 3rd (1981) Differential changes in bone mineral density of the appendicular and axial skeleton with aging: relationship to spinal osteoporosis. J Clin Invest 67:328–335

Treloar AE (1981) Menstrual cyclicity and the pre-menopause. Maturitas 3:249–264

Campbell TL (1993) Research reports: marriage and health. Fam Syst Med 11:303–309

Williams K, Umberson D (2004) Marital status, marital transitions, and health: a gendered life course perspective. J Health Soc Behav 45:81–98

Booth A, Amato P (1991) Divorce and psychological stress. J Health Soc Behav 32:396–407

Gerstel NRC, Rosenfield S (1985) Explaining the sumptomatology of separated and divorced men and women: the role of material conditions and social networks. Oxford J 64:84–101

Rosen CJ, American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. (2009) Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Washington, D.C.

Mora S, Goodman WG, Loro ML, Roe TF, Sayre J, Gilsanz V (1994) Age-related changes in cortical and cancellous vertebral bone density in girls: assessment with quantitative CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 162:405–409

Nilsson M, Ohlsson C, Mellstrom D, Lorentzon M (2009) Previous sport activity during childhood and adolescence is associated with increased cortical bone size in young adult men. J Bone Miner Res 24:125–133

Ott SM (1991) Bone density in adolescents. N Engl J Med 325:1646–1647

Lauderdale DS, Rathouz PJ (2003) Does bone mineralization reflect economic conditions? An examination using a national US sample. Econ Hum Biol 1:91–104

Adler NE, Ostrove JM (1999) Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don’t. Ann N Y Acad Sci 896:3–15

American Psychological Association (2000) Resolution on poverty and socioeconomic status. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant numbers 1R01AG033067, R01-AG-032271, and P01-AG-020166. The research was further supported by the following grants M01-RR023942 (Georgetown), M01-RR00865 (UCLA), from the General Clinical Research Centers Program and 1UL1RR020511 (UW) from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Crandall received support from the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller-Martinez, D., Seeman, T., Karlamangla, A.S. et al. Marital histories, marital support, and bone density: findings from the Midlife in the United States Study. Osteoporos Int 25, 1327–1335 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2602-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2602-4