Abstract

Smoking has a profound impact on tumor immunity, and nicotine, which is the major addictive component of smoke, is known to promote tumor progression despite being a non-carcinogen. In this study, we demonstrate that chronic exposure of nicotine plays a critical role in the formation of pre-metastatic niche within the lungs by recruiting pro-tumor N2-neutrophils. This pre-metastatic niche promotes the release of STAT3-activated lipocalin 2 (LCN2), a secretory glycoprotein from the N2-neutrophils, and induces mesenchymal-epithelial transition of tumor cells thereby facilitating colonization and metastatic outgrowth. Elevated levels of serum and urine LCN2 is elevated in early-stage breast cancer patients and cancer-free females with smoking history, suggesting that LCN2 serve as a promising prognostic biomarker for predicting increased risk of metastatic disease in female smoker(s). Moreover, natural compound, salidroside effectively abrogates nicotine-induced neutrophil polarization and consequently reduced lung metastasis of hormone receptor-negative breast cancer cells. Our findings suggest a pro-metastatic role of nicotine-induced N2-neutrophils for cancer cell colonization in the lungs and illuminate the therapeutic use of salidroside to enhance the anti-tumor activity of neutrophils in breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neutrophils or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are the most abundant leukocyte (50–70%) in human circulation1. They play a critical role in inflammation and in host defense against microbial infections2. In recent years, they are also being recognized as a part of the immune reaction to modulate tumor growth and metastatic progression3. However, the exact role of neutrophils in tumor progression has been a matter of debate as neutrophils were shown to possess both pro- and anti-tumor properties3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Importantly, a high circulating neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a robust biomarker of poor clinical outcome in various cancers17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Indeed, a large meta-analysis of 8563 breast cancer patients found that an increased NLR is associated with an adverse overall- and disease-free survival, specifically within triple-negative breast cancer25. In contrast, other studies linked neutrophil markers to better survival rates in various cancer patients26,27,28,29,30. These conflicting observations stem from the existence of phenotypically heterogeneous and functionally versatile populations within neutrophils that govern how they respond to the environmental cues31. Growing number of evidences indicate that long-term effects of environmental contaminants, such as cigarette smoke have pervasive effects on immunity and health of the smokers due to its adverse effects on both the innate and adaptive immune systems32,33,34,35. In contrast, cigarette smoking was found to induce EMT36 in lung cancer through activation of signaling pathways such as STAT3, AKT, and NF-kB37,38,39. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that LCN2 expression is sustained in the lungs of rats and plasma of COPD patients exposed to cigarette smoke40,41. Intriguingly, there is a strong indication that nicotine, a major component in cigarette smoke, significantly contributes to smoke-induced immunosuppression by attenuating NK cell activity, T-cell proliferation, macrophage antigen processing activity, and dendritic cell number42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. In addition, epidemiological studies also suggest a significant association of cigarette smoking/nicotine with an increased risk of various cancers51,52. It has also been reported that there is a significant association of cigarette smoking with increased lung metastatic burden in women with invasive breast cancer53,54,55 that increased the risk by 18% and lower survival rate by 33% at diagnosis56,57. However, the insidious role of nicotine and its potential direct effects on neutrophils in breast cancer lung metastasis is yet poorly understood. In this study, we addressed this question using a systematic approach, by analyzing the effects of nicotine-associated inflammation in breast-to-lung metastasis. We have shown that nicotine skew neutrophil polarization in the pre-metastatic niche and promotes metastatic colonization of breast cancer by enhancing cancer cell plasticity thereby facilitating tumor progression.

Results

Nicotine-induced neutrophils infiltrate in premetastatic lungs and enhance metastasis

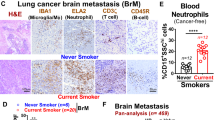

To assess the association between cigarette smoking and the development of pulmonary metastasis among breast cancer patients, we performed retrospective pan-analysis of three previously reported breast cancer cohorts53,54,55,58 with smoking history that comprised a total of 1077 cancer patients. We found that current or ex-smokers have significantly higher lung metastasis incidence compared to the never-smokers (Fig. 1A). Tumor-promoting effects of nicotine on primary tumor growth has been well established59,60, however, its mechanistic impact on distant metastasis is yet poorly characterized. Moreover, given the paucity of reliable data of nicotine dose, we identified the human-relevant physiological concentration of nicotine by examining the serum level of cotinine, the primary metabolite of nicotine, and a biomarker of tobacco smoke exposure, in mice injected with 2 mg/kg of nicotine in time-dependent manner and found that the cotinine level is comparable with adult smokers serum cotinine level compared to never-smokers as previously described61 (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Therefore, we administered 2 mg/kg nicotine to the mice every other days by i.p. injection as earlier reported62,63,64. Next, we examined the role of nicotine in spontaneous and experimental metastasis models by injecting 4T1 and E0771 mouse mammary cancer cell models to assess spontaneous and experimental metastasis in syngeneic Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice with or without i.p. injection of nicotine (every other day till the endpoint) followed by monitoring the tumor growth (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Figs. 1B and 2A). We found that nicotine exposure significantly increased the lung metastatic burden by >100-fold in both spontaneous (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 2B) and experimental (Supplementary Fig. 1C) metastasis, in contrast to less than 10-fold increase in primary tumor growth (Fig. 1D, E, Supplementary Figs. 1D and 2C, D). Notably, nicotine significantly promoted the number of metastatic nodules thereby decrease lung-metastasis-free survival as compared to control group (Supplementary Fig. 1E, F). To identify which immune cell type(s) in the tumor environment were affected by nicotine and contributed to differential outgrowth of primary and metastatic tumors, we examined the composition of neutrophil (ELA2), macrophage (F4/80), and NK (NKp46) cells in primary and metastatic tumors of control and nicotine-treated mice by immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Figs. 1G and 2E). Among these innate immune cells, macrophages were the most abundant population, comprising ~25% (4T1) and ~18% (E0771) in primary tumor and ~5% (4T1) and ~3% (E0771) in metastatic lungs, respectively (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Figs. 1G and 2E). Importantly, neutrophils (Polymorphonuclear cells) were the major cell population in metastatic lungs (~40% in 4T1 and ~27% in E0771) of nicotine-treated mice (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Figs. 1G and 2E). These results imply that nicotine may play a critical role in pre-conditioning of the lung immune microenvironment for metastatic colonization. To test this hypothesis, we employed an experimental pre-metastasis mouse model, which is independent of cancer cell dissemination or intravasation. Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice were pre-exposed to nicotine (2 mg/kg) or PBS via intraperitoneal injection for 10 days followed by intravenous injection of luciferase-expressing 4T1 or E0771 mouse mammary carcinoma cells (Fig. 1H, Supplementary Fig. 2F). The mice did not receive nicotine after the tumor cell injection. We found that the pre-exposure of nicotine significantly increased the lung metastatic burden by >100-fold compared to control mice (Fig. 1I, J, Supplementary Fig. 2G, H). Importantly, the mice pre-exposed to nicotine showed significantly increased number of neutrophils in circulation and in the lungs before injection of cancer cells (premetastatic lung), and their numbers progressively increased during metastatic outgrowth (metastatic lung) after intravenous tumor implantation (Fig. 1K, Supplementary Fig. 1H, I). To further validate this result, we analyzed peripheral blood of smokers (n = 12) and non-smoking (n = 12) cancer-free human subjects (see Supplementary Data 2) to determine the number of peripheral neutrophils (CD15+veSSChi). Our results revealed that smokers had significantly higher number of circulating neutrophils compared to never-smokers (Supplementary Fig. 1J).

A Lung-metastasis incidence in breast cancer patients cohort (n = 1077) comprising both never and current or ex-smokers (two-sided Fisher exact test with relative risk 1.35 and CI 1.06/1.72). B Upper panel: Schematic diagram for spontaneous metastasis. Mouse mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells (204) were orthotopically implanted into mice MFP followed by i.p. injection of PBS (n = 7) or nicotine (n = 6) every other day till the endpoint. Lower panel: Representative images of in vivo primary tumor (top) and ex vivo metastatic lungs (bottom). C Ex vivo quantification of lung metastasis in PBS (n = 7) or nicotine-treated (n = 5) mice by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) at the endpoint (unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p = 0.01). D In vivo growth of primary tumor in PBS (n = 7) or nicotine-treated (n = 6) mice as quantified by BLI (two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *p = 0.04, ***p = 0.0001). E Primary tumor weight in PBS (n = 7) or nicotine-treated (n = 5) mice (unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p = 0.02). F Kaplan–Meier analysis of lung metastasis-free survival in PBS (n = 7) or nicotine-treated (n = 6) mice [log-rank (Mantel–Cox test), **p = 0.001]. G Quantification of IHC staining [number of cell infiltrated/high power field (HPF)] in primary tumor and metastatic lungs in PBS or nicotine-treated mice (n = 5 mice/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0002, ****p < 0.0001, *p = 0.04, p = 0.57). H Upper panel: Schematic diagram for premetastatic treatment with nicotine. Balb/c mice were intraperitoneally injected with PBS or nicotine (2 mg/kg, n = 8/group) every other day till day 10, followed by i.v. injection of 4T1 cells (104) into tail vein. Lower panel: Representative images of in vivo (top) and ex vivo metastatic lungs (bottom). I, J In vivo and ex vivo quantification of lung metastasis incidence in PBS or nicotine-pretreated mice by BLI [n = 8 mice/group, two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (in vivo), *p = 0.04, ***p = 0.0001, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (ex vivo), *p = 0.01]. K Representative H&E and IHC images of neutrophils (ELA2) in PBS (control) or nicotine-pretreated premetastatic (w/o tumor cell) and metastatic lungs (w/ tumor cells) (n = 3/individual experiment; scale bar: 100 µm). All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. ns, not significant; MFP, mammary fat pad; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous.

The effect of nicotine abstinence in the context of metastasis has not been well understood. Therefore, to address this issue, we pretreated mice with nicotine for 10 days followed by injecting 4T1 cells in Balb/c mice 1 day, 15 days, or 30 days after quitting nicotine treatment and assessed the tumor burden and neutrophils level in tumor-bearing and tumor-free mice. Our results indicate that even after quitting nicotine for 30 days, the risk of developing tumor growth and distant metastasis was not prevented, implying an ongoing risk of metastasis in breast cancer patients with smoking history (Supplementary Figs. 3A–E and 4A–D). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that persistent exposure of nicotine generates an inflammatory microenvironment in the lungs characterized by an influx of activated neutrophils that creates a favorable premetastatic niche.

Depletion of nicotine-activated neutrophil decreases lung metastasis

To examine the functional contribution of nicotine-activated neutrophils to metastatic progression, we performed neutrophil depletion experiment under nicotine-treated or untreated setting by injecting the anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8) monoclonal antibody, which specifically depletes Ly6G+ neutrophils but not monocytes12,65. After 24 h of the first nicotine and anti-Ly6G treatment, 4T1 cells were injected intravenously into the mice (Fig. 2A). A significant inhibition in lung metastatic burden was observed in neutrophil-depleted mice compared to isotype (IgG)-treated mice (Fig. 2A–D). On the other hand, lungs of isotype (IgG)-treated tumor-bearing and tumor-free mice under nicotine treatment were significantly infiltrated by activated neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) compared to the control mice, and their proportion was remarkably reduced in lungs of anti-Ly6G treated mice (Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. S5A–C). Moreover, neutrophil depletion significantly inhibited the number of metastatic nodules in lungs and prolonged the lung metastasis-free survival of these animals (Fig. 2F, G). A significant inhibition of circulating neutrophils was also observed in tumor-free mice pretreated with nicotine compared to control mice (isotype (IgG)-treated) (Supplementary Fig. S5D, E). These results further confirmed that nicotine exposure induced neutrophil accumulation in lungs and strongly promoted lung metastatic incidence.

A Upper panel: Schematic diagram of neutrophil depletion experiment. 4T1 cells (104) were intravenously injected into the tail vein of Balb/c mice as indicated with or without i.p. injection of nicotine (2 mg/kg) every other day plus either isotype or anti-Ly6G antibody injection every 3 days. Lower panel: Representative images of in vivo (top) and ex vivo lung metastasis (bottom). B In vivo quantification of lung metastasis incidence with or without nicotine plus isotype or anti-Ly6G treated Balb/c mice by BLI (n = 14 for isotype and n = 15 for anti-Ly6G, two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ****p < 0.0001, p = 0.45, *p = 0.01). C Ex vivo quantification of lung metastasis with or without nicotine plus isotype or anti-Ly6G treated Balb/c mice by BLI at the endpoint (n = 14 for isotype and n = 15 for anti-Ly6G, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p = 0.006, **p = 0.003). D Flow cytometric quantification of lung infiltrating CD11b+ cells (neutrophils) in control, tumor-bearing nicotine-free, nicotine-treated tumor-free, and tumor-bearing mice treated with isotype or anti-Ly6G (n = 3 mice/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0001, **p = 0.001, p = 0.10, **p = 0.002, ***p = 0.0006, p = 0.68). E Flow cytometric quantification of total neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and monocyte (CD11b+Ly6C+) in control (tumor and nicotine-free), tumor-bearing nicotine-free, nicotine-treated tumor-free, and tumor-bearing mice treated with isotype or anti-Ly6G antibody (n = 3 mice/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ****p < 0.0001, *p = 0.01, **p = 0.007, **p = 0.003, ***p = 0.0001, ***p = 0.0002, p = 0.12). F Average number of lung metastases nodules with or without nicotine plus isotype or anti-Ly6G treated Balb/c mice (n = 14 for isotype and n = 15 for anti-Ly6G, unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p = 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). G Kaplan–Meier analysis of lung metastasis-free survival with or without nicotine plus isotype or anti-Ly6G-treated mice [log-rank (Mantel–Cox test), *p = 0.01, ***p = 0.0002]. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. ns, not significant; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous.

Nicotine promotes neutrophil polarization/activation to N2 phenotype in a STAT3-dependent manner

To gain further insight into the functional properties of nicotine-treated neutrophils, we assessed in vitro polarization of human and mouse primary neutrophils using N1-/N2-associated markers66,67. We found that the nicotine treatment significantly skewed neutrophils toward N2-type (CD206, CCL2, ARG2) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). This polarization of neutrophils was also evident in lungs of tumor-free or tumor-bearing mice treated with isotype/anti-Ly6G used in Fig. 2 (Supplementary Fig. 6C). Because nicotine was able to reprogram neutrophils in vitro and in vivo, we next attempted to identify transcription factor(s) that are activated in neutrophils during this process. We examined microarray data of N1-/N2 neutrophils and cross-referenced with transcription factor database66,68. Our analysis revealed that the expression of STAT3 transcription factor was most significantly upregulated in N2 neutrophils compared to N1-neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 6D). We then examined whether STAT3 downstream signaling signature69 was activated in neutrophils using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) in N1-/N2-neutrophil expression profile66. STAT3 activation signature was indeed significantly enriched in N2-neutrophil compared to N1-neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 6E). We further validated this finding by using human primary and HL-60 neutrophils that showed upregulation of STAT3 expression upon nicotine treatment (Fig. 3B). Importantly, we found a significant downregulation of STAT3 and p-STAT3 in nicotine-activated neutrophils in the presence of STATTIC, a known STAT3 inhibitor, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. 6F, G). However, we did not observe diminished STAT3 expression in cancer cells that were treated with STATTIC at the same dose (Supplementary Fig. 6H). We also examined the polarization of neutrophils (HL-60) upon nicotine treatment in the presence or absence of STATTIC using N1-/N2-associated markers. We found that nicotine treatment in the presence of STATTIC significantly downregulated the N2-associated markers (Supplementary Fig. 6I). To further validate this result, we treated HL-60 cells with STAT3-specific siRNA in the presence or absence of nicotine. We found that STAT3 knockdown led to a significant decrease in the expression of N2 markers (Supplementary Fig. 6J). Furthermore, to examine the direct functional effect of N2-neutrophil on lung metastasis in vivo, we performed adoptive transfer of N2-neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) isolated from bone marrow of naive, non-tumor-bearing Balb/c mice treated with nicotine for 10 days (Fig. 3D; Supplementary Fig. 7A, B). As shown in Fig. 3D–G; Supplementary Fig. 6K, when treated with both nicotine and STATTIC, adoptive transfer of N2-neutrophils led to a significant increase in lung metastasis burden. We also examined the expression of relevant N1 and N2-neutrophil markers in lung metastatic tumor by immunofluorescence analysis. We found that both nicotine and adoptive transfer of N2-neutrophils induced infiltration of N2-neutrophil (CD206) in metastatic tumors compared to nicotine plus STATTIC-treatment group, which predominantly showed N1-neutrophil infiltration (NOS2) (Fig. 3H, I). Importantly, similar results were obtained from premetastatic experiment where mice pre-exposed with nicotine showed significantly increased N2-neutrophil (CD206) accumulation in the lung, and their numbers progressively increased in metastatic lung (Supplementary Fig. 7C, D). Furthermore, we analyzed peripheral blood of smoker (n = 12) and non-smoking (n = 12) cancer-free human subjects to determine the status of circulating N1/N2 neutrophils. We found that smokers had significantly higher percentage of circulating N2-neutrophils (LDN) than N1 (HDN) compared to never-smokers (Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). In addition, we found that LDN conditioned media significantly increased the growth of 4T1 tumor cells compared to HDN conditioned media treated cells (Supplementary Fig. SF8C–F). We also found that p-STAT3 expression was significantly increased in mice premetastatic lungs/neutrophils, which was reversed by STATIC treatment, as well as in smoker’s lung metastasis lesion (Supplementary Fig. SF9A–C). These results suggest that the observed increase in lung metastasis upon exposure to nicotine was facilitated by STAT3-activated N2-neutrophils that promoted subsequent formation of metastasis.

A, B Human primary neutrophils and HL-60 were treated with or without nicotine (1 µM) for 12 h. RNA were prepared and examined for the expression of N1 (CD95, NOS2, CCL3), N2 (CD206, CCL2, ARG2) markers and for STAT3 expression by qRT-PCR. β-Actin was used as a normalization control [n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p = 0.001, *p = 0.01, *p = 0.03, **p = 0.005, ***p = 0.0003 (primary), *p = 0.01, ***p = 0.0002 (HL-60)]. C HL-60 neutrophils were treated with nicotine (1 µM) or STATTIC (1 µM) for 24 h, and examined for p-STAT3 expression by western blot. GAPDH was used as controls (n = 3 individual experiment/group). D Left panel: Schematic diagram for adoptive transfer (ADT) of nicotine-polarized N2-enriched neutrophils. 4T1 cells (104) were intravenously injected into tail vein of athymic nude mice followed by i.p. injection of nicotine (2 mg/kg, n = 6) every other day till day 9 or nicotine plus STATTIC (10 mg/kg, n = 13) every other day from day 9 to 18. At day 20, adoptive transfer was performed with N2-enriched neutrophils (107 cells) derived from bone marrow of control or nicotine-treated Balb/c mice as described in “Methods”. Right panel: Representative images of in vivo (top) and ex vivo metastatic lungs (bottom). E, F In vivo and ex vivo quantification of lung metastasis incidence in nicotine (n = 6) or nicotine plus STATTIC (n = 7) or nicotine plus STATTIC plus adoptively transferred N2-neutrophils (n = 6) [two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (in vivo), *p = 0.04, **p = 0.01, p = 0.67, ***p = 0.001, p < 0.0001, and unpaired two-tailed t-test (ex vivo), *p = 0.01, *p = 0.02]. G Average number of lung metastases nodules (n = 6 for nicotine, n = 7 for nicotine plus STATTIC and n = 6 for nicotine plus STATTIC plus N2-ADT, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ****p < 0.0001, *p = 0.04). H Representative H&E (left panel) and immunofluorescence images (right panel) of N1 (NOS2+) and N2 (CD206+) neutrophils in metastatic lung sections of nicotine or nicotine plus STATTIC or nicotine plus STATTIC plus adoptively transferred N2-neutrophils (n = 3/individual experiment; scale bar: 100 µm). I Quantification of immunofluorescence staining for N1 (NOS2+) and N2 (CD206+) neutrophils for the panel (H) (n = 3 mice/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p = 0.005, ***p = 0.0008, ****p < 0.0001). All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. ns, not significant; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous.

Nicotine-polarized N2 neutrophils promote mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition

Both epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) play key roles in metastatic colonization70, and stromal and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment were shown to have significant impact on this tumor cell plasticity71. To test the effect of N2-neutrophil on these processes, we first treated human, mouse primary neutrophils as well as immortalized human neutrophils (HL-60) with or without nicotine and then harvested the conditioned medium (CM) to treat mesenchymal-like MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1a breast cancer cells. We found that CM from nicotine-induced N2-neutrophils strongly promoted MET phenotype in both cancer cells (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 10A, B). This epithelial transition of MDA231 and MCF10CA1a was further confirmed by increased expression of E-cadherin, EpCam, and Keratin18 and reduced expression of Vimentin, N-cadherin, and ZEB172 (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Fig. 10C). Furthermore, we examined E-cadherin expression in matched primary breast and lung metastatic tumor from spontaneous metastatic and neutrophil-depleted mice that were used in Figs. 1G and 2A, and found that both primary breast and metastatic lungs from nicotine-treated groups showed increased E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, lung metastasis from neutrophil-depleted mice showed reduced E-cadherin expression compared to isotype-treated lung (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, when we treated cancer cells with CM collected from nicotine-treated fibroblast (MRC-5), we did not observe any changes in EMT/MET markers, whereas nicotine-treated monocytes (THP1) CM increased E-cadherin expression to a lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. 10D). Treatment of epithelial-like MCF7 cells with nicotine-induced neutrophil CM also did not alter Vimentin and E-cadherin expression compared to mesenchymal-like MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1a cells (Supplementary Fig. 10D). Since nicotine is reported to directly potentiate cancer cell EMT59, we also examined its direct effect on cancer cells. As expected, the nicotine treatment in cancer cells (MDAMB231, MCF10CA1a, and MCF7) resulted in significant increase in EMT markers (Vimentin, ZEB1) relative to untreated control cells (Fig. 4D). Similar results were observed when 4T1 cells were treated with CM derived from mouse primary neutrophils treated with or without nicotine (Supplementary Fig. 11A, B). Furthermore, we observed a significant increase in tumor cell growth upon treatment with CM derived from nicotine-induced primary human neutrophils compared to the control, as assessed by clonogenic assay (Fig. 4E). We also examined the expression of nicotine-specific α4 and β2 receptors on multiple breast cancer cells (MCF7, MDAMB231, MCF10CA1a, and BT549) and human/mouse primary neutrophils. Interestingly, both α4 and β2 receptors were selectively overexpressed in human and mouse primary neutrophils in comparison to breast cancer cells (Fig. 4F). These results indicate that the nicotine-activated N2-neutrophils are sufficient enough to reprogram the cancer cells to undergo MET to acquire the epithelial phenotype and promote metastatic colonization in the lung.

A Upper panel: Experimental setup for obtaining control or nicotine-polarized neutrophil conditioned medium. Lower panels: Morphological changes in MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1a cells treated with the indicated CM. B MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1a cancer cells were treated with the indicated nicotine-activated neutrophil CM for 24 h. Cells were then examined for the expression of epithelial (E-cadherin, EpCam, Krt18) and mesenchymal (Vimentin, N-cadherin, ZEB1) markers by qRT-PCR and western blot. β-Actin was used as input control for qRT-PCR. Representative immunoblots shows expression of E-cadherin, Vimentin, and ZEB1 in MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1a. GAPDH was used as a control for western blot [n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0003, *p = 0.02, *p = 0.01, **p = 0.007 (MDAMB231), ***p = 0.001, ***p = 0.0008, **p = 0.001, ***p = 0.0004 (MCF10CA1a)]. C Representative IHC images for E-cadherin in metastatic lungs derived from the experiment in Figs. 1B and 2A (n = 3/individual experiment; scale bar: 100 µm). D MDAMB231, MCF10CA1a, and MCF7 cancer cells were treated with or without nicotine (1 µM) for 24 h followed by examining the expression of epithelial (E-cadherin, EpCam) and mesenchymal (Vimentin, ZEB1) markers by qRT-PCR. β-Actin was used as a control for normalization [n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p = 0.03, ****p < 0.0001, **p = 0.003 (MDAMB231), ***p = 0.0003, **p = 0.001, **p = 0.007, *p = 0.03 (MCF10CA1a), **p = 0.004, ***p = 0.0002, **p = 0.001 (MCF7)]. E MDAMB231 cancer cells were treated with either nicotine or with conditioned medium derived from nicotine-treated human primary neutrophils. Cells were then examined for their colony-forming ability (n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p = 0.003). F Expression of α4 and β2 nicotine receptors in primary neutrophils (human and mouse) and in various breast cancer cells (MCF7, MDAMB231, MCF10CA1a, BT549) was examined by qRT-PCR. β-Actin was used as a control for normalization (n = 3 individual experiment/group). All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Secreted LCN2 by nicotine-activated N2 neutrophil promotes epithelial plasticity of breast cancer cells

To identify the secretory factor(s) from nicotine-induced N2 neutrophil that mediated MET of cancer cell, we performed expression profile analysis for human primary neutrophils that were treated with or without nicotine using a qPCR array focused on EMT/MET genes. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12A, lipocalin-2 (LCN2) expression was most significantly upregulated in nicotine-activated N2-neutrophils compared to control cells. LCN2 is a secretory glycoprotein and known to be expressed in the neutrophil granules73. We performed ELISA analysis and found that human primary neutrophils and HL-60 cells indeed secreted significantly higher amount of LCN2 when treated with nicotine compared to the non-treated neutrophils or cancer cells (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, we noted significant dose-dependent downregulation of LCN2 in nicotine-treated N2-neutrophils in the presence of the STATTIC (Supplementary Fig. 12B). In addition, we analyzed ENCORI database74 to determine LCN2 functional correlation with ERα, PR, and HER2 expression in breast cancer patients. We found that LCN2 expression was negatively correlated with ERα, PR, and HER2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 12C). To further clarify the role of LCN2 in inducing epithelial phenotype, we treated cancer cells (MDAMB231, MCF10CA1a) with human recombinant LCN2 (hrLCN2). We found that hrLCN2 at low concentration (2.2 µM) induced MET phenotype in cancer cells, and this was further confirmed by strong E-cadherin and low Vimentin expression (Fig. 5B, C). We also examined the effect of CM of nicotine-activated N2 neutrophils on cancer cells. We observed upregulated expression of E-cadherin and KLF4 (hallmarks of MET)75,76 and downregulated Vimentin and phospho-ERK1/2 in cells treated with CM from nicotine-activated N2-neutrophils compared to the control CM. In contrast, an inverse correlation was noted when cancer cells were directly treated with only nicotine (Fig. 5D). Importantly, the EMT induced by nicotine in cancer cells was rescued when treated with hrLCN2 similar to control cancer cells treated with CM from nicotine-induced N2-neutrophils as showed in Fig. 4 panel B (Fig. 5D), indicating that LCN2 is a candidate driver of the epithelial phenotype. Because LCN2 is secreted by nicotine-activated neutrophils, we tested the potential utility of LCN2 as a biomarker for early breast cancer progression in smokers. We quantitated the level of LCN2 in serum and urine level of treatment naïve, stage-II, human hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients (n = 20 for serum and n = 20 for urine) and in cancer-free females (n = 12 for serum and n = 20 for urine) with or without smoking history (see Supplementary Data 3–5). We found significantly higher level of LCN2 in serum and urine of smoking patients as well as in cancer-free smokers compared to non-smoking patients and cancer-free subjects (Fig. 5E, F). To further validate these results, we used a previously published cohort of 23 patients with breast cancer metastasis77. The patients with lung metastasis expressed significantly higher level of LCN2 than the patients with other metastasis (Supplementary Fig. 12D). Moreover, because LRP2/megalin have been reported to bind and mediate the cellular uptake of LCN278,79, we examined its expression in CSC (cancer stem-like cells) cells obtained from MDAMB231 or metastatic breast cancer PDX. We found that LRP2 expression was significantly downregulated in CSC in both breast PDX and cell line (Supplementary Fig. 12E). This was further validated using non-CSC and CSC in cancer patient cohort80 (n = 29) and in our previously published cohort data of 710 patients with breast cancer81 (Supplementary Fig. 12F, G). Interestingly, we observed high LRP2 expression in non-CSC from cancer cell, PDX, and patients tumor as well as in TNBC patients (n = 162) compared to CSC cells and luminal type breast cancer patients (n = 218) from the same groups (Supplementary Fig. 12F, G). Furthermore, to examine the direct functional effect of N2-neutrophil secreted LCN2 on promoting MET and lung metastasis, we applied the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to knockout the LCN2 in neutrophils. When tested in vitro, we observed a significant decrease in MET phenotype and tumor cell growth upon treatment with CM derived from nicotine-induced LCN2 knockout neutrophils (HL-60) compared to the control cells (wild) (Supplementary Fig. 13A, B). However, when LCN2 knockout cells were adoptively transferred into nude mice followed by intravenous injection of MCF10CA1a human mammary cancer cells, loss of LCN2 significantly associated with decreased lung metastasis burden compared to wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 13C–G). Together, these data suggest that nicotine-activated N2-neutrophils exert their tumor-promoting effect in part by inducing LCN2.

A LCN2 protein level in CM derived from nicotine-treated (1 µM) or untreated neutrophils (human primary and HL-60 cells) and breast cancer cells (MDAMB231) was quantified by ELISA (n = 3 individual experiment/group, one-way ANOVA ***p = 0.0003, **p = 0.03, p = 0.08). B MDAMB231 and MCF10CA1 cells were treated with 2.2 µm human recombinant LCN2 and the expression of E-cadherin and Vimentin was examined by qRT-PCR and western blot. β-Actin and GAPDH were used as controls [n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p = 0.009, **p = 0.001 (MDAMB231), **p = 0.002, ***p = 0.0006 (MCF10CA1a)]. C MDAMB231 cells were treated with or without recombinant LCN2 (2.2 µM) for 24 h, followed by assessing E-cadherin and Vimentin expression by immunocytochemistry (n = 3 individual experiment/group; scale bar: 50 µM). D MDAMB231 cells were treated with indicated CM or nicotine alone or with human recombinant LCN2 (2.2 µM) to rescue from suppressive effect of nicotine after 24 h. Cells were then examined for the expression of E-cadherin, Vimentin, pERK1/2, ERK2, and KLF4 by western blot. GAPDH was used as a control (n = 3 individual experiment/group). E, F LCN2 was quantified in serum and urine samples of stage-II, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients (n = 20 for serum and n = 20 for urine) and cancer-free females subjects (n = 12 for serum and n = 20 for urine) with or without smoking history by ELISA [unpaired two-tailed t-test, ****p < 0.0001 (serum), **p = 0.006, ***p = 0.0007 (urine)]. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Salidroside selectively suppresses lung metastasis by blocking nicotine-induced N2 neutrophil polarization

The aforementioned results suggest that nicotine activates N2-neutrophil and supports aggressive cancer cells to metastasize to the lung. Therefore, identifying a drug that specifically block neutrophil polarization would be a promising therapeutic approach to treat breast cancer lung metastasis. Toward this end, we used natural compound library (n = 124) to screen compounds that selectively block N2-neutrophil polarization upon nicotine treatment by assessing ARG2 expression using duplex qPCR, followed confirming the result by ELISA (Fig. 6A). We found salidroside as the top candidate compound that was most effective in suppressing ARG2 expression and secretion (Fig. 6B, C). To further assess salidroside suppressive effect on nicotine-activated N2-neutrophil, HL-60 neutrophils were treated with nicotine plus salidroside and examined for N1-/N2-associated markers. We found significant decrease in N2-markers (CD206, ARG2) in contrast to N1-markers (CD95, NOS2). Similarly, we also observed downregulation of active p-STAT3/STAT3 by salidroside under nicotine treatment (Fig. 6D, E). This indicates the efficacy of salidroside in blocking the nicotine-mediated N2-neutrophil polarization toward N1-neutrophil. We then tested in vivo efficacy of salidroside by intravenously injecting MCF10CA1a breast cancer cells into nude mice followed by intraperitoneal administration of nicotine (2 mg/kg) with or without salidroside (20 mg/kg) every other days till endpoint. We found that salidroside significantly decreased nicotine-mediated lung metastatic burden and number of lung metastases nodules thereby increasing lung metastasis-free survival (Fig. 6F–J). We also examined the expression of relevant N1 and N2-neutrophil markers in lung metastatic tumor by immunofluorescence analysis. We found that nicotine induces infiltration of N2-neutrophil (CD206+) in metastatic tumors compared to nicotine plus salidroside treatment group, which predominantly showed N1-neutrophil infiltration (NOS2+) (Supplementary Fig. 14A, B). Furthermore, salidroside treatment did not show any notable toxicity in the mice nor reduce the cell viability of cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 14C–E), indicating the neutrophil-specific effect of salidroside. We also examined the expression of N1 and N2-neutrophil markers in tumor-free premetastatic lung by immunofluorescence analysis. We found that nicotine-induced infiltration of N2-neutrophils (CD206) in premetastatic lungs and salidroside treatment reversed these neutrophils to N1-neutrophil (NOS2) (Supplementary Fig. 14F, G). Taken together, these results strongly suggest salidroside as a promising therapeutic drug that could be useful in preventing or managing smoking-induced breast cancer lung metastasis.

A Experimental diagram for screening of natural compound library containing 124 compounds. B Top 6 natural compounds that showed more than 1000 fold reduction of ARG2 expression by duplex qRT-PCR. C ARG2 protein in CM derived from HL-60 neutrophils was examined by ELISA after treating with or without salidroside (0.1 µM) in the presence or absence of nicotine (1 µM) (n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p = 0.01, **p = 0.001, *p = 0.04). D Nicotine and nicotine plus salidroside treated cells were examined for expressions of N1 (CD95, NOS2) and N2 (CD206, ARG2) markers by qRT-PCR. β-Actin was used as a control for normalization (n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0001, ****p < 0.0001). E Cells in (C) were examined for expressions of STAT3 and p-STAT3 by qRT-PCR and western blot. β-Actin and GAPDH were used as controls (n = 3 individual experiment/group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0009, *p = 0.03, ***p = 0.0002). F Upper panel: Schematic diagram for experimental metastasis. MCF10CA1a cells (504) were intravenously injected into tail vein of athymic nude mice followed by i.p. injection of nicotine (2 mg/kg, n = 7) or nicotine plus salidroside (20 mg/kg, n = 7) every other day till the endpoint. Lower panel: Representative images of in vivo (top) and ex vivo metastatic lungs (bottom). G–J In vivo quantification of lung metastasis (n = 7 individual mice/group, two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *p = 0.03, ****p < 0.0001) (G), average number of lung metastases nodules (n = 7 individual mice/group; data are presented as mean ± S.E.M., *p = 0.01, unpaired two-tailed t-test) (H), ex vivo quantification of lung metastasis (n = 7 individual mice in each group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, ***p = 0.0006) (I), and lung metastasis-free survival in nicotine or nicotine plus salidroside treated nude mice [log-rank (Mantel–Cox test), ***p = 0.0003] (J). All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous.

Discussion

Identifying mechanisms by which premetastatic niches contribute to tumor outgrowth is an area of active investigation; however, little is known whereby extrinsic environmental factor(s) dictate organ-specific metastatic progression, against a background of massive attrition of the disseminated tumor cells. Here we provide compelling evidence that chronic exposure of nicotine plays a critical role in initiating neutrophil recruitment and premetastatic niche formation by skewing neutrophil toward a tumor-supporting phenotype. Previous studies on premetastatic niche formation have revealed complex interplay fostered by tumor-mobilized and recruited BMDCs and several types of immune cells82. These cells within the premetastatic niche remodel the local microenvironment by secreting inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proangiogenic molecules, thus supporting tumor cell colonization, proliferation, and promoting tumor metastasis83,84,85,86,87,88. Furthermore, recent findings highlighted the emerging role of neutrophils in premetastatic niche formation during inflammatory responses4,9,12,89,90. Interestingly, in our study, we found that pre-exposure of nicotine progressively increased neutrophil accumulation followed by significant increase in lung metastatic burden. Moreover, we found remarkable increase in the number of neutrophils even after withdrawal of nicotine, which is in good agreement with an earlier study showing significant association of high leukocyte count with smoking that consistently persists after quitting smoking91. Furthermore, elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in healthy smokers and in patients with breast cancer has been found to be associated with systemic inflammation and poor prognosis25,92. We also found significant number of circulating neutrophil among cancer-free smokers, which is in concordance with an earlier study reporting the increase number of peripheral neutrophils in active smokers and in patients with stable COPD93,94. In addition, previous studies have reported that nicotine augments anti-apoptotic signaling and chemotactic migration of neutrophils, leading to their accumulation and promotion of local tissue damage95,96. Intriguingly, a recent study showed that inhalation of nicotine in e-cigarette triggers neutrophil activation and thereby promotes inflammatory response97. These observations are consistent with our finding of pro-metastatic role of nicotine in generating pro-inflammatory milieu within the lungs. Further characterization of activated influx of pro-tumor neutrophils revealed permissive action of nicotine in providing hospitable microenvironment to attract tumor cells to a target organ (lung) and aid their growth or survival that contribute to premetastatic niche formation.

Neutrophil plays a critical role in modulating the growth of primary tumors and progression to metastatic disease3. They exhibit anti-tumor functions98 such as direct tumor cell killing12,99,100, functioning as antigen-presenting cells101, and recently found antibody-mediated trogoptosis102. Neutrophils have also been implicated in promoting metastasis in various cancers by secreting leukotrienes4, FGF2103, Bv887, or by undergoing the process of NETosis89. Altogether, these evidences raised the possibility for the existence of phenotypic heterogeneity and functional versatility within the neutrophils that govern how they respond to the environmental cues31,104,105. In addition, compelling evidence from earlier studies105,106,107 have clearly identified distinct populations of circulating neutrophils (N1 and N2) in the blood of tumor-bearing mice and in cancer patients. Moreover, a recent study108 showed that N2-neutrophils interact with circulating tumor cells (CTC) within the bloodstream to promote metastatic niche formation. Similarly, circulating N2-neutrophils have also been reported in non-cancer inflammatory pathologies such as stroke, myocardial infarction and systemic lupus erythematosus109,110,111. Our study has demonstrated that nicotine induced N2-polarization of neutrophils under pathologically relevant concentrations commonly found in the blood of cigarette smokers33. Notably, we found that nicotine-induced N2-neutrophils selectively colonized the lungs of tumor-free mice and established premetastatic niche for tumor cells that were later implanted in these mice leading to significant increase in lung metastatic burden. In contrast, robust reduction in lung metastatic burden and neutrophil accumulation was observed when neutrophils were depleted or when nicotine-activated STAT3 signaling was pharmacologically targeted. This could be partially explained by increase in nicotine binding to neutrophils with subsequent upregulation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, as previously documented112. In addition, we found significantly increased number of peripheral N2-neutrophils in active cancer-free smokers. This correlates well with impaired immune response observed in smokers as classical neutrophil function was attenuated in the N2-neutrophils due to downregulation of antigen processing pathways and chemokines66. Conversely, earlier studies showed increased neutrophil motility and chemotactic ability during smoking-associated inflammatory conditions113,114. Intriguingly, a recent study showed that neutrophils from mice with early-stage tumors had a higher level of spontaneous migration compared to neutrophils from late-stage tumors, indicating a role of phenotypic switch mediated by the local microenvironment115. Overall, our study revealed STAT3-dependent mechanism of neutrophil polarization under nicotine-primed environment with pro-tumor properties. It also highlighted the crucial role of nicotine in driving N2-neutrophils influx into the lungs as an early prerequisite step that direct the tropism of breast cancer cells during premetastatic niche formation.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and its reversed process, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), are fundamental evolutionarily conserved processes in embryonic development and tissue repair, but confer malignant properties to carcinoma cells116. Earlier studies have established EMT as a prerequisite step to escape from primary tumor but the process is insufficient and may even be detrimental for early colonization as tumor cells need to recover some epithelial characteristics required for metastatic outgrowth117,118,119,120,121,122. Moreover, recent studies have shown that MET can be induced by either cell-intrinsic or stromal components70,71,123,124,125,126,127,128,129. However, direct mechanistic evidence that define interaction between immune and cancer cells during smoking-induced overt inflammation with possible contribution to support cancer cell colonization at premetastatic niche remained poorly understood. Here, we showed that nicotine-activated neutrophils secrete glycoprotein lipocalin-2 (LCN2) which facilitate functional reversion of mesenchymal cancer cells into epithelial phenotype (MET) in a paracrine manner which is an essential step for metastatic colonization as previously described130. Notably, we found elevated serum and urine LCN2 levels in actively smoking breast cancer patients and cancer-free females further supporting our in vitro findings. Moreover, we found a negative correlation of LCN2 expression with ERα, PR, and HER2 expression in primary breast tumors (Supplementary Fig. 12C), which is consistent with a previous finding that overexpression of LCN2 led to reduced ERα expression in MCF7 breast cancer cells131. We also found that LCN2-null neutrophils were less effective in inducing MET and metastasis compared to wild-type neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 13A–G) that suppresses the effect of nicotine on MET by upregulating E-cadherin via modulating ERK-KLF4 signaling axis, suggesting it as a candidate driver of the epithelial phenotype132,133,134. Interestingly, Ouzounova et al. recently showed that granulocytic cells (gMDSC), a subset of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, are capable of reverting EMT in breast cancer128. Although both neutrophils and gMDSCs were shown to exhibit phenotypic and functional similarities135, tumor-supporting role of nicotine-activated neutrophils provide direct experimental proof that distinguish them from the immunosuppressive function of gMDSCs reported in their study. Interestingly, nicotine was previously found to directly potentiate EMT in various cancer cells59. However, it should be noted that the LRP2 receptor for LCN278 was found to be expressed at a low level in cancer stem cells in breast cancer. In addition, a recent study showed that EMT cells were more susceptible than MET cells to neutrophil cytotoxicity while promoting efficient seeding in premetastatic lung136 thereby highlighting the importance of environmental stimulations in establishing lung metastasis. Collectively, our findings suggest spatiotemporal regulation of cancer cell plasticity by nicotine-activated N2-neutrophils that switches mesenchymal tumor cells into epithelial lineage to efficiently grow at the premetastatic niche.

By screening natural compound library, we identified salidroside as a potent inhibitor of nicotine-induced N2 conversion of neutrophils. Salidroside is a natural antioxidant originally extracted from medicinal food plant Rhodiola rosea137 and possesses potential anti-inflammatory138, anti-viral139, and anti-cancer140 properties. Salidroside was previously shown to exhibit tumor-suppressive activity by modulating multiple pathways including, Notch1141, STAT3138, and PI3K/AKT142. However, these direct tumor cytotoxic effects mediated by salidroside required relatively high dose both in vitro and in vivo140. In this study, we found that low dose of salidroside effectively suppressed nicotine-induced polarization of neutrophils to N2 phenotype and enhanced its N1 phenotype by decreasing activated STAT3 expression. In addition, we did not find any notable effect of low-dose salidroside on cancer cells growth. Importantly, we found that salidroside administration following nicotine exposure significantly reduced lung metastatic burden thereby inhibited lung metastasis. Considering the in vitro and in vivo inhibitory effect of salidroside on nicotine-induced neutrophil activation and their minimum toxicity at the low dose, salidroside could offer a potential therapeutic utility for long-term prevention and suppression of metastasis, particularly for cancer patients with past and current smoking history. While other components in cigarette smoke may contribute to metastasis, their role in metastasis remains limited. To our knowledge, no study till date has investigated a potential association between nicotine and its direct effects on neutrophils in breast cancer lung metastasis.

Our findings describe the mechanisms that underlie nicotine’s pro-metastatic functions to promote breast cancer lung metastasis by skewing polarity of neutrophils in premetastatic lung followed by stimulating cell–cell communication through secretory LCN2. Importantly, we identified salidroside as a potential therapeutic agent that specifically enhance anti-tumor activity of neutrophils in the lungs (Fig. 7).

Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human breast carcinoma cell lines, MCF10CA1a, MDAMB231, MCF7, BT549, lung fibroblast cell line, MRC-5, monocyte cell line, THP1, and mouse breast carcinoma cell line, 4T1, E0771 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Human neutrophilic promyelocyte cell line, HL-60143 was provided by Wake Forest Institutional Cell Bank Repository. All cells were cultured in their respective medium either RPMI-1640 or DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, streptomycin (100 mg/ml), and penicillin (100 units/ml). Human primary neutrophils were purchased from Astarte Biologics and were maintained in serum-free AIM-V medium (Gibco). Mouse primary neutrophils were obtained from Balb/c mice. In brief, femur and tibia of euthanized mice were removed and flushed using a 25-gauge needle filled with PBS. The resulting cell suspension was gently disaggregated and passed through a 40 µm cell strainer (Corning) to produce a single-cell suspension. All red blood cells were hypotonically lysed by adding 10 mL of 0.2% NaCl for 30 s to remove contaminating erythrocytes, followed by neutralization with 10 mL of 1.6% NaCl. Neutrophils were then washed in Hanks’s balanced salt solution and further purified using MACS-based neutrophil isolation kit (Milteyni Biotec–130-097-658) as per manufacturer’s recommendation and cultured in serum-free AIM-V medium. All cells were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and were routinely tested for the absence of Mycoplasma. Recombinant human lipocalin-2 (hrLCN2) were purchased from R&D System.

Human clinical samples

Urine

A total of 40 urine samples from stage-II hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients with or without smoking status (median age 59 and 56 yr) were procured from NCORP Sample Repository Facility after obtaining written informed consent from all subjects at Wake Forest Cancer Center. Similarly, a total of 20 urine samples from cancer-free female subjects with or without smoking status (median age 42.5 and 45 yr) were purchased from Lee Bio-solution after obtaining written informed consent from all subjects. All the samples were collected in a labeled sterile container and immediately centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 11 × g to obtain supernatant and were stored at −20 °C till analysis. All samples were collected under the Wake Forest School of Medicine IRB (Institute Review Board) approved protocol IRB00031311.

Serum

A total of 20 serum samples from stage-II hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients with or without smoking status (median age 54 and 51 yr) were purchased from Biosample Repository Facility after obtaining written informed consent from all subjects at Fox Chase Cancer Center and stored at −80 °C until analyzed. Similarly, a total of 24 fresh serum from cancer-free control subjects with or without smoking status (median age 45 yr) were purchased from BioIVT after obtaining written informed consent from all subjects and processed immediately for neutrophil isolation144 followed by flow cytometry quantification or used as serum for LCN2 analysis as described hereafter. All samples were collected under the Wake Forest School of Medicine IRB (Institute Review Board) approved protocol IRB00031311.

Mouse neutrophil isolation

Mouse whole blood was collected at the indicated time points by cardiac puncture using heparinized (Sigma) syringe. The blood was diluted with an equal volume of PBS containing 0.5% BSA and subjected to Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) gradient (1.077). Neutrophils were collected from the plasma-1077 interface (low-density neutrophil; LDN) as well as from RBC pellet fraction (high-density neutrophil; HDN). RBCs were eliminated by hypotonic lysis. For functional analysis, neutrophils were further enriched using MACS-based neutrophil isolation kit (Milteyni Biotec) as per manufacturer’s recommendation and were stained with CD11b (catalog no. 103012) and Ly6G (catalog no. 17-9668-82103012) fluorescence-labeled antibody. Flow cytometry data were collected on Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

Human neutrophil isolation

Human neutrophils were isolated as previously described144. In brief, fresh human whole blood was mixed with an equal volume of HBSS and was layered on top of Ficoll-Hypaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1:1 ratio and centrifuged. Neutrophils were collected from the plasma −1.077 interface (low-density neutrophil; LDN) as well as from RBC pellet fraction (high-density neutrophil; HDN). RBCs were eliminated by hypotonic lysis. For functional analysis, isolated neutrophils were stained with APC-labeled anti-human CD15145 (1:100, eBioscience, catalog no. 17-0158-42) or NOS2-PE (1:100, Novus Biologicals, catalog no. NBP2-22119) and CD206-FITC (1:100, BioLegend, catalog no. 321103) antibodies. Flow cytometry data were collected on Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were done in accordance with a protocol approved by the Wake Forest Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free unit on a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle. The animal rooms are provided with 100% fresh, HEPA filtered air at 10–15 air changes per hour. Room temperatures are controlled by reheat units within each room, and are maintained within the range of 70 °F ± 2 °F. The Humidity levels are controlled globally, and it is maintained between 30 and 70%. To examine the effect of nicotine, we employed spontaneous metastasis assay. In brief, luciferase-labeled 4T1 tumor cells (204 cells/mice) or E0771 tumor cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mice) were resuspended in 50:50 solutions of PBS and Matrigel (Corning) and injected into the fourth mammary fat pad of 5–6-week-old BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice. To confirm successful injection, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) from whole body of the mice was immediately measured using Xenogen IVIS imaging system (Caliper Life Science) under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia at the indicated times. One day after implantation, mice were divided into two groups (8 mice/group), the first group was administered with nicotine (2 mg/kg, every second day, Sigma-Aldrich) while second group received PBS through intraperitoneal injection. The primary tumor and metastasis outgrowth were monitored twice a week using BLI. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed, primary tumors were resected, weighed and the presence of metastatic lesions on the lungs was evaluated by ex vivo bioluminescent imaging and histological analysis. Images were analyzed using Living Image Software (Caliper). For experimental metastasis assay, luciferase-labeled 4T1 cells (104) or E0771 cells (504) were injected into the tail vein of BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice followed by segregation into two groups as described in the spontaneous metastasis assay. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed and metastatic tumor burden on lungs were processed as described in the spontaneous metastasis assay. Similarly, luciferase-labeled MCF10CA1a cell (504) were injected into the tail vein of athymic nude mice. One day after implantation, mice were divided into two groups (8 mice/group), the first group was administered with nicotine (2 mg/kg, every other day) while second group received nicotine plus natural compound Salidroside (20 mg/kg, every other day, Sigma-Aldrich) through intraperitoneal injection till the endpoint. The metastasis outgrowth was monitored twice a week using BLI. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed, the presence of metastatic lesions on the lungs were evaluated by ex vivo bioluminescent imaging and histological analysis. Images were analyzed using Xenogen IVIS imaging system (Caliper Life Science).

For experiments involving neutrophil adoptive transfer, luciferase-labeled 4T1 cells (104) were injected into the tail vein of athymic nude mice. One day after implantation, all mice were administered with nicotine (2 mg/kg, every other day) through intraperitoneal injection. At day 9, mice were randomly divided into two groups, the first group (n = 6) continued with nicotine while second group (n = 13) received nicotine plus STATTIC (10 mg/kg, every third day, Sigma-Aldrich) through intraperitoneal injection. At day 18, second group was further divided randomly into two groups after stopping STATTIC treatment. The first group (n = 7) continued with nicotine while second group (n = 6) received nicotine plus N2-neutrophil adoptive transfer at day 20 as described under adoptive transfer of N2-neutrophil section. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed, the presence of metastatic lesions on the lungs were evaluated by ex vivo bioluminescent imaging and histological analysis. For experiments requiring biochemical analysis such as AST, blood was obtained from the euthanized mice by cardiac puncture and the serum was obtained by centrifugation. All mice were randomized before the experiment, blindly selected before injection, and sample size was chosen based on power analysis.

In vivo neutrophil depletion

To deplete neutrophils, female Balb/c mice (n = 8) were intraperitoneally injected with neutrophil-depleting antibody (anti-Ly6G 200 μg per mouse, clone 1A8; BioXCell, catalog no. BE0075-1) before 4T1 tumor cell injection and continued every third day at the indicated time points. Matching mouse IgG2A (1:100, BioXcell, catalog no. BE0085) served as isotype control. At the endpoint, mice were sacrificed and flow cytometry was used to verify the efficacy of neutrophil depletion. Data were collected on Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

In vivo adoptive transfer of CD11b+Ly6G+ N2-neutrophils

For adoptive transfer of N2-neutrophils, tumor-free Balb/c mice pre-exposed to nicotine were used to isolate neutrophils from bone marrow (BM). In brief, femur and tibia of sham (n = 3) and nicotine-treated (n = 4) naive, non-tumor-bearing euthanized mice were removed and flushed using a 25-gauge needle filled with PBS. The resulting cell suspension was gently disaggregated and passed through a 40 µm cell strainer (Corning) to produce a single-cell suspension. All red blood cells were hypotonically lysed by adding 20 mL of 0.2% NaCl for 20 s, followed by neutralization with 20 mL of 1.6% NaCl. Neutrophils were then isolated using MACS-based neutrophil isolation kit (Milteyni Biotec) as per manufacturer’s recommendation and characterized for N2 phenotype as described in “Flow cytometry” section. Recipient mice were injected i.v. with single injection of N2 neutrophils (10 × 106) resuspended in ice-cold HBSS in a volume of 200 µl at the indicated time point.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical analysis on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue section of breast and lung from control and nicotine-treated mice was carried out using antibody specific for neutrophil elastase (ELA2). Briefly, 5 µM tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and heated at 80 °C for 20 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen exposure. They were then treated with 3% H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase activity and further blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h. The sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibody [ELA2 (1:100, Abcam, catalog no. ab68672), F4/80 (1:100, eBioscience, catalog no. 14-4801-82), NKp465 (1:100, BioLegend, catalog no. 137601), E-cadherin (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 3195)] for overnight at 4 °C. After washing with Tris-buffered saline/0.1% Tween-20, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit-specific IgG (Dako Corp.). The sections were washed extensively and DAB substrate chromogen solution was applied followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin.

For immunofluorescence, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections were obtained from control and/or STATTIC or salidroside treated metastatic lung with or without nicotine and handled according to a standard immunofluorescent paraffin-embedded tissue staining protocol. In brief, after deparaffinization in xylene and re-hydration, antigen retrieval was carried out in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) at 95 °C for 30 min. They were then treated with 3% H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase activity and further blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h. The sections were then washed with PBS containing 0.15% glycine and were incubated either with anti-mouse NOS2-PE (1:100, Novus Biologicals, catalog no. NBP2-22119), biotinylated-CD206 (1:100, BioLegend, catalog no. 141713) and p-STAT3 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9145), fluorescently conjugated with Alexa-488 or Alexa-647 secondary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4410 and 4412), Ly6G-APC (1:1000, eBioscience, catalog no. 17-9668-82) or with anti-human NOS2-PE (1:100, Novus Biologicals, catalog no. NBP2-22119), CD206-FITC (1:100, BioLegend, catalog no. 321103) antibodies followed by 12 h incubation at 4 °C. Both FFPE sections were mounted in VECTASHIELD (Vector Lab) mounting medium with DAPI and the fluorescence images were captured by a fluorescent microscope (Keyence BZ-X700). All image quantification was done by ImageJ software (version 1.8.0).

Generation of conditioned medium

Condition medium (CM) were prepared by seeding 0.5–1 × 106 THP1, MRC-5, and HL-60 cells with or without 1 μM Nicotine (Sigma-Aldrich) in regular culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h, cells were washed by PBS and incubated further for 24 h in serum-free culture condition. The harvested CM was then centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells and debris and store at −80° C. To prepare primary neutrophil CM, 1–2 × 106 freshly procured neutrophils (LDN and HDN) were washed with HBSS and cultured overnight in serum-free RPMI or AIM-V medium in the presence or absence of 1 μM nicotine. After overnight incubation, the harvested neutrophil conditioned medium was then centrifuged to remove cells and debris at 300 × g for 10 min and stored at −80° C.

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNAs was extracted from indicated cells using TRIzol reagent (Qiagen). The concentration of cell-free total RNAs was quantified using NanoDrop 2000 UV-spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) by using a Reverse Transcription Supermix kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The cDNA was then amplified with a pair of forward and reverse primers for the genes listed in Supplementary Data 1 created by using Microsoft Excel (version 2016). Results were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-Actin. The thermal cycling conditions composed of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of PCR using the following profile: 94 °C for 30 s, 62 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s using Bio-Rad CFX connect.

ARG2 duplex RT-qPCR was performed on HL-60 cells treated with or without nicotine in presence or absence of natural compound library (n = 124) using Taqman Gene Expression Cells-to-CT kit as per manufacturer’s recommendation on Bio-Rad CFX connect. Results were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-Actin labeled with VIC dye.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described146. Briefly, protein was extracted from the cells using RIPA buffer, quantified by NanoDrop 2000, resolved by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then electrotransferred to PVDF membrane. Primary antibodies against STAT3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4904), phospo-STAT3 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9145), E-cadherin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 3195), Vimentin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 5714), ZEB1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 70512), phospo-ErK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4370), total-Erk (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9102), KLF4 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-20691), GAPDH (1:10,000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 5174) were used. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 7076) or anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 1706515) secondary antibody was used and the antigen-antibody reaction was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Imager 600).

Colony formation assay

In brief, 100 cancer cells per well were plated in six-well plates in triplicates and cultured with nicotine (1 µM) or CM from human primary neutrophils treated with nicotine or HDN/LDN CM from mouse primary neutrophils for 7 days as indicated before staining viable colonies with 0.5% crystal violet solution (Sigma-Aldrich).

ELISA

LCN2 (Lipocalin-2) protein levels in serum and urine of breast cancer patient serum and cancer-free females with or without smoking status as well as in conditioned medium derived from control and nicotine-treated cells were determined using human Lipocalin-2 ELISA Kit as per manufacturer’s recommendation (RayBiotech). Finally, LCN2 concentration was determined at 450 nm wavelength by EMax Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). Standard curves were obtained from values generated from known concentrations of human LCN2 provided by the kit and LCN2 concentration in each sample is interpolated from this standard curve. For assaying ARG2 (Arginase 2), conditioned medium (CM) from indicated groups (HL-60 ± nicotine ± FDA-compound library) were subjected to human ARG2 ELISA kit as per manufacturer’s recommendation (AVIVA Systems Biology). Finally, ARG2 concentration was determined at 450 nm wavelength by EMax Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). Standard curve was made using known concentrations of human ARG2 provided by the kit and ARG2 concentration in each sample was interpolated from this standard curve.

Cotinine levels in serum were determined using mouse Cotinine ELISA Kit as per manufacturer’s recommendation (MyBioSource). Standard curve was made using known concentrations of mouse cotinine provided by the kit and cotinine concentration in each sample was interpolated from this standard curve. Cotinine concentration was determined at 450 nm wavelength by EMax Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA).

MTS assay

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS Promega) assay was used to determine viability of the indicated cells. Briefly, 5000 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The cells were then treated with indicated drugs in dose and time-dependent manner. Thereafter, MTS solution was added to each individual well and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The media was then removed and 150 µl DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm by EMax Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). Five replicate wells were included in each analysis and at least three individual experiments were conducted.

STAT3 siRNA transfection

Commercially available 19 mer STAT3 siRNA (GenBank Accession Number: NM_003150) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The cells were transfected with STAT3 siRNA (10 nM) using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s recommendation. The sense and anti-sense sequence of STAT3 siRNA is provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Gene set enrichment analysis

GSEA was performed by generating the Gene MatriX file (.gmx) by using published STAT3 activation signatures69. The Gene Cluster Text file (.gct) was generated from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=GSE101584)66 by separating neutrophils based on their status of polarization. The Categorical class file (.cls) was generated based on the STAT3 activation scores and we used GPL6885 as the chip platform.

Clinical dataset analysis

For survival analyses, overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survivals (DMFS), stratified by expression of the gene of interest, were presented as Kaplan–Meier plots and tested for significance using log-rank tests. The analysis was performed according to the instructions as described earlier (http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service)147.

Flow cytometry

For neutrophil analysis, lungs of isotype (IgG), anti-Ly6G-treated tumor-bearing, and tumor-free mice were excised and minced with fine scissors in PBS containing 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin and the suspension was filtered gently through a 70 µm cell strainer, followed by 40 µm cell strainer. The single-cell suspension was spun down, resuspended in PBS, and proceeded for MACS-based neutrophil isolation (Milteyni Biotec) as per manufacturer’s recommendation. The isolated single-cell suspension was fluorescently stained with anti-mouse CD11b-PECy5 (1:1000, BioLegend, catalog no. 103012), Ly6G-APC (1:1000, eBioscience, catalog no. 17-9668-82), Ly6C-FITC (1:1000, BioLegend, catalog no. 128006), and matched IgG2a isotype control (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4410 and 4412). Cell debris and dead cells were excluded from the analysis based on scatter signals and propidium iodide (PI) fluorescence. Data were collected on Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

For N2-neutrophils characterization, bone marrow of tumor-free Balb/c mice pre-exposed to nicotine were processed to isolate purified CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils as described in in vivo N2-neutrophil adoptive transfer section. The isolated single-cell suspension was fluorescently stained with mouse-specific CD11b-PECy5 (1:1000, BioLegend, catalog no. 103012), Ly6G-APC (eBioscience, 1:1000, catalog no. 17-9668-82), Ly6C-FITC (1:1000, BioLegend, catalog no. 128006), NOS2-PE (1:100, Nous Biologicals, catalog no. NBP2-22119), biotinylated-CD206 (1:100, BioLegend, catalog no. 141713), fluorescently conjugated with Alexa-488 or Alexa-647 secondary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4410 and 4412). Matched mouse IgG2A (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 61656) served as isotype control. Cell debris and dead cells were excluded from the analysis based on scatter signals and propidium iodide (PI) fluorescence. Data were collected on Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

For CSC analysis, single-cell suspension was fluorescently stained with anti-CD44-APC (1:20,000, BioLegend, catalog no. 103012) and anti-EpCam-PE (1:500, eBioscience, catalog no. 12-9326-42) for 20 min followed by examining marker positive population (CD44high,EpCamhigh) using Accuri C6 analyzer and analyzed using C6 software (BD Biosciences).

Gene knockout

LCN2 knockout was carried out with CRISPR/Cas9 system. In brief, HL-60 neutrophils were transfected with Cas9 protein V2 (ThermoFisher) and guide RNA sequence (sgRNA: GAAGUGGUAUGUGGUAGGCC) that flank the target sequence. Single-cell clones were picked by limit dilution based on Synthego’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism (version 7.0). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. The p value was calculated by an unpaired Student t test or ANOVA with corresponding numbers (n) as indicated in the figures and corresponding legends. Gene correlation analysis was calculated by linear regression analysis. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was calculated by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Significant between each group were represented as *p < 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 unless otherwise indicated).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The GEO dataset (GSE101584, GSE11078, GSE7513, GSE12276, GSE2034, GSE2603, GSE5327, and GSE14020), TFcheckpoint, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis referenced during the study are available in a public repository from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds; https://www.tfcheckpoint.org; http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service website. All the other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mestas, J. & Hughes, C. C. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J. Immunol. 172, 2731–2738 (2004).

Kolaczkowska, E. & Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 159–175 (2013).

Coffelt, S. B., Wellenstein, M. D. & de Visser, K. E. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 431–446 (2016).

Wculek, S. K. & Malanchi, I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature 528, 413–417 (2015).

Tazawa, H. et al. Infiltration of neutrophils is required for acquisition of metastatic phenotype of benign murine fibrosarcoma cells: implication of inflammation-associated carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 2221–2232 (2003).

Takeshima, T. et al. Key role for neutrophils in radiation-induced antitumor immune responses: Potentiation with G-CSF. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11300–11305 (2016).

Spiegel, A. et al. Neutrophils suppress intraluminal NK cell-mediated tumor cell clearance and enhance extravasation of disseminated carcinoma cells. Cancer Disco. 6, 630–649 (2016).

Spicer, J. D. et al. Neutrophils promote liver metastasis via Mac-1-mediated interactions with circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 72, 3919–3927 (2012).

Nozawa, H., Chiu, C. & Hanahan, D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12493–12498 (2006).

Lopez-Lago, M. A. et al. Neutrophil chemokines secreted by tumor cells mount a lung antimetastatic response during renal cell carcinoma progression. Oncogene 32, 1752–1760 (2013).

Huh, S. J., Liang, S., Sharma, A., Dong, C. & Robertson, G. P. Transiently entrapped circulating tumor cells interact with neutrophils to facilitate lung metastasis development. Cancer Res. 70, 6071–6082 (2010).

Granot, Z. et al. Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell 20, 300–314 (2011).

Finisguerra, V. et al. MET is required for the recruitment of anti-tumoural neutrophils. Nature 522, 349–353 (2015).

De Larco, J. E., Wuertz, B. R. & Furcht, L. T. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4895–4900 (2004).

Colombo, M. P. et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) gene transduction in murine adenocarcinoma drives neutrophil-mediated tumor inhibition in vivo. Neutrophils discriminate between G-CSF-producing and G-CSF-nonproducing tumor cells. J. Immunol. 149, 113–119 (1992).

Ponzetta, A. et al. Neutrophils driving unconventional T cells mediate resistance against murine sarcomas and selected human tumors. Cell 178, 346–360 (2019).

Zaragoza, J. et al. High neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio measured before starting ipilimumab treatment is associated with reduced overall survival in patients with melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 174, 146–151 (2016).

Yalon, M. et al. Elevated NLR may be a feature of pediatric brain cancer patients. Front Oncol. 9, 327 (2019).

Terashima, T. et al. Blood neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Hepatol. Res. 45, 949–959 (2015).

Peng, B., Wang, Y. H., Liu, Y. M. & Ma, L. X. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 3098–3106 (2015).

Iimori, N. et al. Clinical significance of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in endocrine therapy for stage IV breast cancer. In Vivo 32, 669-675 (2018).

Gu, X. et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in prostate cancer: evidence from 16,266 patients. Sci. Rep. 6, 22089 (2016).

Grenader, T. et al. Derived neutrophil lymphocyte ratio is predictive of survival from intermittent therapy in advanced colorectal cancer: a post hoc analysis of the MRC COIN study. Br. J. Cancer 114, 612–615 (2016).

Cho, H. et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer and predicts survival after treatment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 58, 15–23 (2009).